-

-

Geaux-Kwik

By Johnny Lee Brown-Sampayo

Illustration by Wesley Allsbrook

Family of Pineville mechanic pleads for answers

Marcus Wells, 39, was last seen around 6:00 p.m. on June 17, leaving his job at RiverBend Auto Repair in Pineville.

“He’s always been reliable, always,” said Mia Wells, Marcus’ wife. “He’d never choose to leave his family.”

Wells is the fourth person to disappear in Rapides Parish since February. The Pineville Police Department declined to comment, but Mrs. Wells says that no one in the department has allowed her to file a missing persons report.

“I keep on calling,” she said, “and they keep on telling me he’s grown and he can be anywhere he likes.”

– from the Rapides Parish Register, Thursday, June 26, 2025I never planned on driving the Louisiana backroads at 8:30 at night with a storm on the way, no cell service, and a gas tank that’s damn near empty. Oak and pine trees tower over the narrow, two-lane highway as we drive Keyonna’s 2012 Tacoma deeper into the dense country darkness. I search for a sign pointing to the campsite around every bend, but I’ve only seen faded mile markers for the last half hour.

“Why can’t you admit we’re lost?” I ask her. “What if we run out of gas? What if we get pulled over?”

My nerves are worsening by the minute. We were supposed to be there by now.

“What if you stop worrying about things that haven’t happened yet?” Keyonna retorts.

She’s driving with her left hand, leaning back in her seat, fingers tapping along to the stereo. We danced to this song at a house party last week. Music makes me forget our quarrels and instead, lets me enjoy her hands on my hips and her warm, soft body against mine. I try to hold onto that sensation while we drive through this country dark, further into the woods of Rapides Parish.

Keyonna’s favorite band holds retreats out here a couple times a year. I think making people drive multiple hours from home just for bugs and dirt and no running water is rude, but Andie’s the frontwoman and the boss, and the campsite is close to her hometown. She invited Keyonna to try out for lead guitarist after the last guy moved to Austin. Every time I called Keyonna for the past two weeks, she’d been rehearsing. I feel guilty for wishing we hadn’t come, but spending a stormy night in rural Louisiana with a bunch of white people we don’t know sounds like ready-made trouble.

“Black people have gone missing here,” I argue. “There was an article in a local paper from, like, two weeks ago about a guy who completely vanished. No sign of him or his car. I’m not disappearing out here because you’re being prideful.”

“‘Prideful’ is the most Southern way you could’ve said that,” she deflects.

Keyonna is from Los Angeles and has teased me about what she calls my “Southernisms” since the day we met.

I stare straight ahead as my stomach gets tighter and tighter. There’s no telling when the rain will start. When it does, I’d like to be inside the shitty discounted tent Keyonna picked up at the last minute.

In the glow from the dash, I watch her glance down. Probably at the gas gauge.

I can’t help but ask, “You didn’t get gas yesterday, huh?”

Keyonna sighs.

“I didn’t have time,” she admits through a tense jaw. “I figured we’d have enough to get out here, and I’d fill up on the way back.”

I take a deep breath to stifle my irritation, but before I can answer back, we round a bend. At the end of a long, straight stretch of highway sits a gas station, bright as a lighthouse.

“Guess we’re in luck,” I say, relief loosening the knots in my stomach.

Keyonna skids into the narrow driveway and kills the engine. The radio cuts off, making room for the silence to grow between us. The only sound comes from the rushing, whistling wind. Nothing moves outside except the twisting branches. We sit still, unease tying us together.

The cramped parking lot holds only four shabby gas pumps. Yellowed flood lights at the corners of the canopy are the only source of light around us. One of them blinks off and on weakly, making shadows–deepen and lighten, deepen and lighten–in a way that makes me feel sick.

“Geaux-Kwik” glows in dull orange neon above the door.

Keyonna chews the inside of her cheek, slowly shoves open her door and jumps out onto the cracked concrete. The thought of either of us being alone makes my insides knot up again, so I follow her. Wind presses my T-shirt flat against my stomach. The fresh, ominous scent of the coming rain fills the air.

Key’s cussing under her breath as I reach her. A peeling orange sticker on the pump commands, “See attendant for gas.”

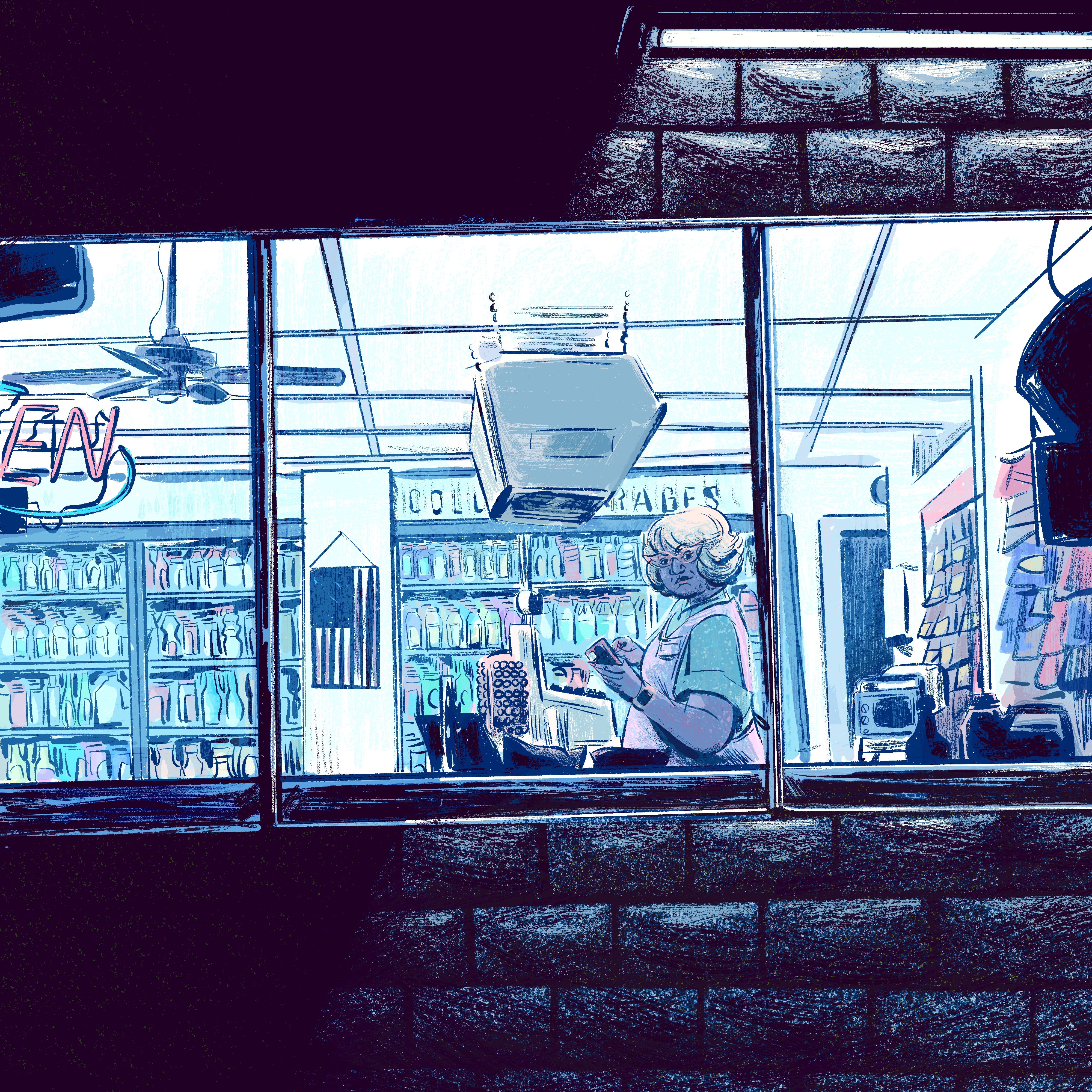

Inside the store, a short, curvy silhouette slides into the grimy window that frames the area behind the counter.

“You sure you don’t wanna wait here?” Keyonna asks. The wind is strong enough to lift her waist-length locs, blowing them back from her face.

“No way.”

She smiles nervously at me and pulls the door open. A shrill bell tinkles over our heads as we squeeze ourselves inside. She wipes her hand on her jeans, like the door handle had something sticky or slimy on it. I try not to think about what it might be. A middle-aged Black woman with a honey-blonde bob watches us from behind the counter. Her makeup is impeccable: smooth foundation that matches her light brown skin; flawless contouring; peachy-orange lipstick; subtle gold eyeshadow over perfectly glued lashes.

“Hey, how ya’ doing?” Keyonna says, setting her keys on the counter and getting her credit card ready.

“How ya’ doing?” She answers. “What can I get you?”

“Forty-five on number one, please, Ms. Leticia,” she says, squinting at the woman’s name tag.

Leticia gives Keyonna an unimpressed once-over before turning to the cash register. Her long coffin nails, the same color as her lipstick, click-clack on the keys.

I glance around while she’s ringing up our total. Three sets of metal shelves hold chocolate bars and chips and sour candies. Looking harder, I realize there’s a thin coating of dust over most of the snacks. A door, marked “Employees Only,” takes up most of the wall opposite the door we came in. The rest of that space is occupied by a narrow fridge, only half-stocked with cold drinks. Keyonna puts her card into the reader and waits. A long beep sounds and frustration clouds her face. Leticia sucks her teeth.

“It’s the weather,” she sighs. “This thing acts up when it storms.”

“You have cash?” Keyonna asks me in a low voice.

Before I can answer that my wallet is still in the truck, Leticia says, “Let me find my manager. He’s got the magic touch. Stay right there.”

She slides out from behind the counter and taps on what must be the door to the office. Without waiting for a response, she sticks her head in and says,

“Zak, can you do that thing with the card reader again?”

“I don’t believe this,” Keyonna mutters. She pulls out her phone. “Still no service. This is already the worst audition ever.”

“Let’s just get out of here,” I murmur, rubbing her arm. “Worry about Andie later. She probably knows plenty people who got lost their first time out here.”

I drop my hand when the manager comes out. Zak is skinny and no taller than five-foot-seven. His light brown hair curls out awkwardly from under a fraying LSU baseball cap. He leans slightly forward as he walks, like he’s stalking deer. He locks the office door, then goes back to texting furiously on a giant Android phone. How the hell does he have service out here?

“Evening, ladies,” he says, looking us over so slowly that I can study his eyes––hard and frosty blue. A strange black spot protrudes from his left iris.

He slips his phone in the pocket of his stained jeans and crouches behind the counter. The card reader goes dark.

“We’ll give it a minute to think about what it’s done,” he chuckles.

“You got it from here?” Leticia asks him. She pulls a small, beige designer purse from under the counter and looks at him with eyebrows raised.

“Sure do. You go on.”

She squeezes behind me and Keyonna, smelling strongly of rose and vanilla, and turns back to Zak at the door.

“I’ll be back for my money tomorrow,” she tells him, rapping her knuckles on the glass with each syllable of “tomorrow.”

“You know I’m good for it,” Zak answers.

He stands back up and turns the card reader to face him. The front door thuds behind Leticia, then something metallic clicks. I look over in time to see Leticia, one hand holding her hair against the wind, slide a key out of the door and into her purse. My entire body clenches. There’s no turn lock on our side, just a keyhole. She’s trapped us in here.

“Hey!” I yell. Before I can think of anything else to say, she’s out of sight.

“Forget Leticia,” Zak drawls. “Her job’s done, and she don’t wanna’ see what’s coming.”

He’s leaning against the wall of cigarettes and miniature liquor bottles, playing with the keys to our truck.

“Listen,” Keyonna croaks, shifting to stand between me and the manager, “we won’t tell anybody about whatever you’ve got going on here. Just give me my keys and let us leave. We don’t want any trouble.”

“That’s too bad,” Zak says. He shoves our keys deep in his pocket with a feral grin. His teeth look strange: long and pointed. “Trouble’s already here.”

The rain must be close because the cars pulling into the parking lot are dripping. Some still have their windshield wipers on. A couple jacked-up pickup trucks, multiple run-down SUVs, and one alarm-red ‘80s muscle car skids into the narrow driveway.

“Didn’t take ’em long tonight,” Zak says, watching the parking lot with satisfaction on his scrawny face.

My brain feels like a machine with something stuck in the gears. Zak has a phone with service. More importantly, he has our keys. Maybe we can take him together; maybe, we can get our keys, his phone, or both.Keyonna jumps when I slide my hand into hers. Darting from Zak to the cars outside, her eyes are wide and shiny from the fear she’s holding in.

I nod my head toward Zak and mouth to Keyonna, “Get. The. Keys.”

Zak is still turned away from us with his arms crossed, humming something. We have to try now. She blinks fast, pushes down her fear, and nods in determination. A bald white man in a sheriff’s uniform walks up to the door and puts a key in the lock. He barges in, gun and all, twirling a silver key ring on one finger and rubbing his stomach.

“Zak-y!” he booms. “Got your text, son. ’Bout time we fed.”

More whites follow him. Middle-aged and younger, some are tanned from days outside and a couple dressed in suits. They all carry a frantic, feral energy I’ve never encountered. They all have Zak’s eyes: those pale, ice-blue glares rake over us as they cram into the tiny store.

“Evening, ladies and gentlemen,” Zak crows. “We got us some new blood tonight.”

The tightly packed crowd cheers, stretching their mouths into jagged caverns. Pointed tongues glide hungrily over their lips.

“What in the fuck?” Keyonna whispers in a high, broken voice.

As we watch, their fingers extend into curved, steel-sharpening talons.

“We’re assembled here tonight,” Zak continues, “for some good, old-fashioned hide-and-seek.”

The crowd whoops at full volume, drowning out the thunder. Zak raises his hands for silence, wiping a string of saliva from his chin.

“My friends, it ain’t no fun to play alone. This sacred ritual we have endured lets us tap into our deepest power – our truest, most dominant nature. When we hunt, we honor that dominance. When we hunt, we honor the forefathers who kept our bloodlines pure!”

More cheers from the restless, jostling bodies. I try desperately to find an escape.

“Let’s get this party started,” a man in the back shouts.

“Hold up,” Zak says, beckoning to the sheriff, “Lester, your gun, please.”

“Aw,” Lester grunts, resting a hand on his holster, “I ain’t gonna use it.”

“For the last time,” an older woman in a skirt suit snaps, “It gives you an unsportsman-like advantage. Turn the damn thing over so we can eat.”

Lester sighs and stalks over to the counter, mouth twisted in annoyance. He unclips the gun and flips it to hand the grip to Zak. Before I can talk myself out of it, I pull free of Keyonna and lunge forward. My hand is inches from Lester’s when my side explodes with pain and I stumble to the floor.

Keyonna screams as one in the assembly laughs, “This one’s got nerve, huh?”

Blood leaks from my abdomen onto my legs. I look up to see a set of dripping claws inches from my face.

“Get up!” the skirt suit woman snarls. She wraps her fingers around my upper arm and pulls. The shredded skin on my side tears even more and I can’t help but scream.

“I won’t be so gentle next time,” she hisses, shoving me at Keyonna. She holds me up as best she can, pressing her hand over my wound.

Zak taps something on the computer behind the counter, then turns back to the room, fangs on full display.

“Y’all ready to play?”

The crowd shrieks and chitters in response. The sheriff starts a chant that the others join, their eyes wide and frenzied with excitement.

Run, monkey, run,

We all wanna eat!

Run, monkey, run,

We all need fresh meat!

They press even closer, pushing us toward the door, chanting louder and louder. Their mouths are watering – someone’s so close that their stinking saliva drips down the back of my neck.

Outside, the thunder claps and the sky splits open at last.

“You got a ten-minute head start,” Zak shouts. “Now go on – go quick.”

The screeching laughter fades into the rain as Keyonna and I stumble out into the storm.

-

Johnny Lee Brown-Sampayo is a Black, queer, New Orleanian who writes at the intersections of these identities. They maintain a blog on Black horror media and the practice of healing personal and collective trauma through this genre; their short fiction has previously appeared on NIGHTLIGHT: A Black Horror Podcast (episode 512). Johnny Lee lives in New Orleans with their husband, mom, and three spicy cats.